A Discussion With James Au, Author of Making a Metaverse That Matters

A Discussion With James Au, Author of Making a Metaverse That Matters

Blogs

•

February 11, 2026

•

Lewis Ward

A Discussion With James Au, Author of Making a Metaverse That Matters

Blogs

•

February 11, 2026

The 20-year metaverse vet shares his thoughts on what's gone right and what's gone wrong relative to the Snow Crash vision

Metaverse platforms have to succeed as communities first before you impose the financial stuff. Because if you put the financial stuff there, people end up…They’re there to make money...You don’t want that. You want people to be, you know, hanging out with each other, meet each other. Like, I would like to be friends with someone from the Philippines and know about them and they know about me. And, you know, all that goes away if you have just this big financial imposition on the whole experience.—James Au

James Au, author of the insightful and entertaining 2023 book, Making a Metaverse That Matters, was a guest on Player Driven in December. Au didn’t pull any punches when it came to a topic that’s been near and dear to his heart for two decades: the metaverse.

Yes, the metaverse.

Despite what you may have read or heard, or perhaps experienced first-hand in recent years, the metaverse is indeed alive and kicking. In fact, according to Au, it’s on a comeback tour now that Meta has taken a huge step back from its 4+ yearlong “all metaverse all the time” messaging and investment strategy (and pivoted to AI).

Au, who hails from Kailua, a beach town not far from Honolulu on the Hawaiian island of O’ahu, has been as enmeshed as anyone in all things metaverse since Second Life debuted in 2003. Author of three books and numerous articles featured in The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, Wired, Gigaom and other publications, Au currently lives in Los Angeles and additionally consults with metaverse-related companies.

The first question that Player Driven host Greg Posner put to Au was how he was drawn into the metaverse at a time when he was surrounded by virtually infinite irl sun and sand.

“I would go surfing or play beach volleyball in the day,” Au responded, grinning wryly. “I love Hawaii and it’s always home. It is paradise.”

“As a hardcore geek, I would, you know, be really wanting to see what the latest game is. You enjoy Hawaii in all its splendor in the daytime, and then you wait until it gets dark when, you know, you get your graphic display working really well. So yeah, I just tried to mix both…the best of the real world, best of the virtual world.”

That sounds rough.

I was excited to be a co-host on this Player Driven episode because I was a Second Life resident (briefly) in the late 2000s, remember the experience with fondness, and I wanted to pick Au’s brain on what this OG metaverse instance was—and is—about in a broad, long-term sense. As an official embedded reporter (Linden Lab, maker of Second Life, hired him to chronicle events and news there) for many years, few people on Earth or in the metaverse are better positioned than Au to put the lay of that particular piece of virtual land into context.

My first question to Au, though, was about a higher-level topic that he raised early in his 2023 book, which he was gracious enough to share with me.

In Making a Metaverse That Matters, Au wrote, there are over half a billion regular metaverse users, led by several social gaming platforms such as Roblox, Minecraft, and Fortnite. These, and their smaller metaverse cousins, “share five core features that are integral and unique,” according to Au, and these generally yield better user experience than the 2D websites and virtual communities most of us grew up with and continue to use today.

Regarding these five metaverse-defining features, Au responded, one was that a “metaverse is a vast virtual world. It’s highly immersive, which could mean a VR headset or no VR headset…It’s either 3D on your screen or on your headset, but mostly it’s going to be, you know, on a flat screen, like on a mobile, or your desktop, or a console.”

The second and third differentiators are that metaverses have “highly customizable avatars and creation tools, which is very important.”

In the book, Au noted that avatars help create a sense that users are part of a virtual world and can be perceived by others in it at the same time. A experiment run at Stanford University years ago, he also noted, showed that most avatar users felt such an intuitive connection with their avatars’ perspective that they recreated unconscious social rules, as if these avatars were an extension of their real-life selves, a key difference from the typical anonymous (well, with cookies) web surfing experience.

Turning to the UGC (user-generated content) angle, Au told us that Roblox, Minecraft, Fortnite, and other metaverse platforms, have deep and rich feature sets that allow users to remake entire worlds or build new ones from scratch (mostly on PCs), and publish them for others to experience and share.

|

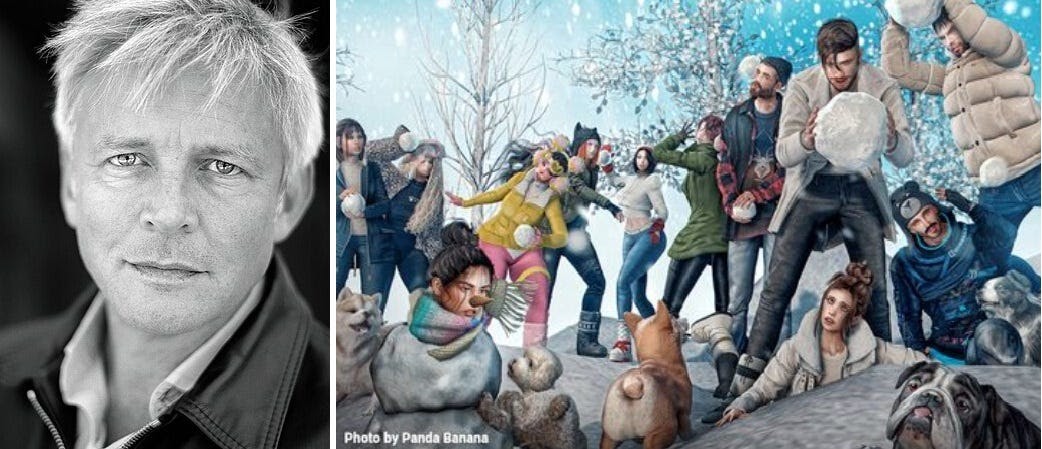

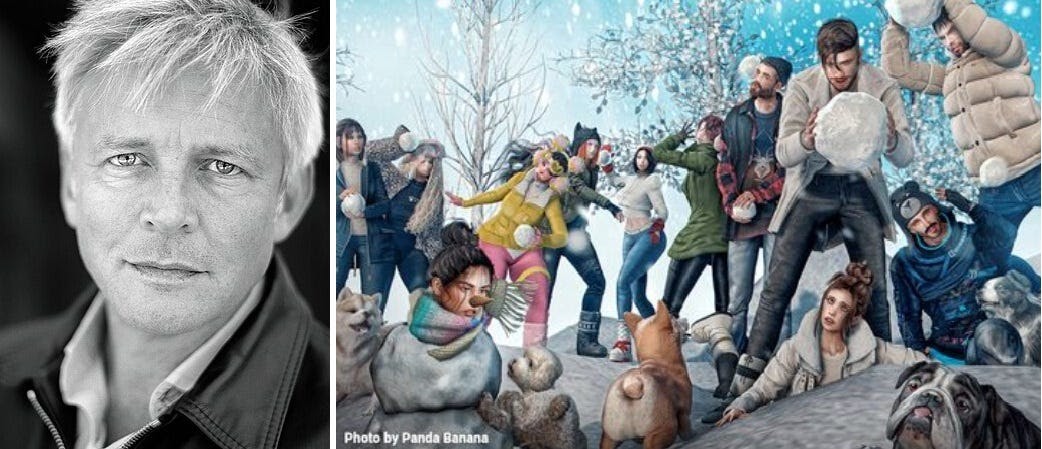

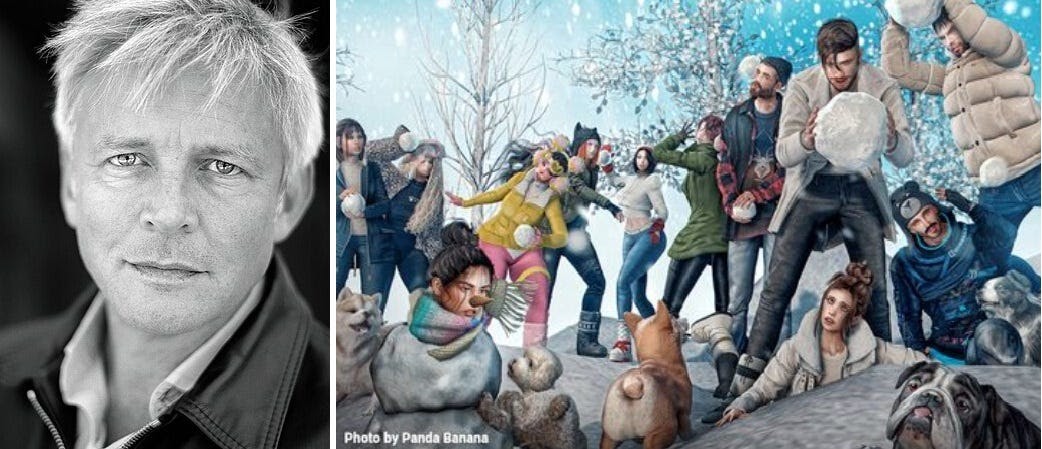

Left to right: Greg Posner, Wagner James Au, Lewis Ward.

The forth differentiator, Au said, is that metaverse platforms are “connected to the real world economy and off-world or non-virtual world technology. So, in practical terms, that means it’s integrated with...The virtual currency…is connected to the real world economy in the sense that you could cash out your virtual currency.”

Check. It’s true that platforms like Roblox, Minecraft, Fortnite and Second Life all support creators who make good irl livings by building objects and experiences that other players/users pay for directly or indirectly. (Player Driven fans may recall that we profiled a Overwolf/CurseForge creator of ARK: Survival Ascended mods who routinely cleared >$15,000 a month last year, so this UGC monetization angle isn’t exclusive to the metaverse platforms.)

Last, Au said that metaverses have “the capacity to contain many millions of people. So one advantage of that is you can meet people from all over the world.”

He underscored the importance of this social angle and also highlighted its accessibility elements.

“A lot of people who use metaverse platforms are physically disabled for many reasons, and are able to connect [there]. For example, there’s technology now…You can connect your brain to a virtual world and can control it there. Or if you’re disabled, you can still have ways of connecting within the virtual world. And, you know, that becomes your social channel in a lot of ways.”

Three of Au’s five metaverse differentiators have ties to their rich social capabilities: avatars, UCG tools, and direct social networking and communication (friends lists, voice and text chat, etc.).

“The thing about avatars,” Au added, “and I say that as part of the definition, ‘highly customizable,’ is, to your point, [that] a lot of people go into a virtual world space and you are engaging with millions of people that are strangers. And so, you know, people are uncomfortable with expressing who they are in real life, often. And so they want to experiment with what their identity is…That’s an also important thing” in metaverses relative to most online communities and websites.

“The game industry is sort of confused why Roblox is really huge,” Au continued. “And I’m, like, pulling my hair out. It’s because it’s a metaverse platform.”

“It’s not only [that] you’re able to create interactive experiences, but you have hundreds of millions of people. There’s 360 million monthly active users in Roblox. And also you have all this high degree of customizability.”

“So, unlike Steam, where you create a game and if you’re to update it, it’s a whole arduous process...[On Roblox] you can adjust it based on literally millions of people interacting with it, and get really interesting interactivity, and then [make] improvements that you can do on the fly.”

Au’s thoughts drifted back to Second Life. That metaverse “is a community. The people, they actually know each other in Second Life, and they end up meeting in real life. There was a Second Life convention. So people would actually go to Chicago or New York or San Francisco to meet people.”

Au believes that the social side of metaverses is a huge factor in their stickiness.

“With the metaverse, it’s other people to a great extent. It’s people that you meet from all walks of life” that’s at the root of why millions of users come back weekly, if not daily, year after year, to these environments.

“So, yeah, those are the five things. And that’s taken directly from [Neal Stephenson’s] Snow Crash, the novel, because that really inspired the whole metaverse wave and it actually envisioned the whole metaverse.”

“Unfortunately, [Meta’s] Mark Zuckerberg and some other folks within the tech industry sort of forgot that that’s what we were all trying to build, and people like [Epic Games’] Tim Sweeney have been trying to build since the early nineties.”

We’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Read on, if you’d like Au’s takes on:

What Second Life, Roblox, and Fortnite have gotten right

Where some prominent metaverse platforms have fallen flat

How leading metaverses can shore up some key shortcomings to help unlock their latent potential

Oh, and if you’re not subscribed to our newsletter, what’s the holdup?

Where Second Life, Roblox, and Fortnite Stand As Metaverse Standard-Bearers

What Second Life did right was getting the community there first, and making sure people really wanted to be there to hang out with each other and to be friends with each other…That’s kind of been the problem with the...I call it the cryptoverse. Virtual worlds that are linked to NFTs or cryptocurrency, none of them have really taken off because of this problem. It’s like, if you are saying that you’re there with the idea, like, in Decentraland, that your property is going to be super valuable at some point, and you can sell it off, then people are only there for the profit motive. They’re not there to hang out with other people and meet other people, and make friends and work on creative projects. So, yeah, they’ve kind of gone nowhere because of that…People are already there for the wrong reasons.—James Au

Two big takeaways from James Au’s assessment of today’s top metaverse examples were that (1) they nail the community support elements and (2) they onboard noobs into the sticky fun and social goo as quickly as possible.

We began by discussion what Second Life got right back in the day.

“It was the first platform to reach mainstream awareness that really was trying to capture the whole metaverse experience,” Au explained to Greg and me. “Everything I mentioned of, you know, highly customizable avatars, creation tools you could [use to] build immediately…”

“This is even before Minecraft. You could actually just construct a 3D, you know, building a castle or a spaceship or whatever, and then there’s physics and there’s scripting so you can actually create, make it interactive. That’s the first, like, actual platform to show all of that and show what was possible, and it immediately got people excited from all walks of life.”

“As a reporter” in Second Life, Au continued, “I met people, like, who are artists and academics and, yeah, people who are not only gamers. They were seeing this. Well, you know, most of them had read Snow Crash, so they saw where this was going.”

Not long after the “eyeballs” arrived in the early- to mid-2000s, companies and nonprofits began showing up and staking out a presence on the platform.

In Second Life, Au recalled, “a lot of companies started putting up headquarters and creating marketing experiences, like American Apparel and Coca-Cola and so on.”

“What they [Linden Lab] got right is really capturing the vision and showing there is an interest in it. And then I go into the flip side of what they didn’t get right.”

“Is Second Life a game?” Au asked. “It’s still this philosophical question that generates a huge amount of arguments…You know, I love Philip Rosedale. He’s brilliant.”

“He’s not a gamer. So, he wanted it to be like a online Burning Man because he’s a big Burning Man guy,” Au explained. “I’ve talked to Philip about that.”

|

Left: Linden Lab founder Philip Rosedale. Right: Avatars in Second Life having a snowball fight…and dancing.

“It’s like, ‘Philip, yeah, Burning Man is really cool, but Only 50,000 people go to Burning Man, and it tends to be fairly wealthy folks. And it’s, like, you’re not going to [get] a whole diverse group of people to go into this thing if you’re going for that Burning Man thing,’” said Au.

“Minecraft launched a few years after Second Life and because it was a fun game experience to start with, now you have schools using it. You have communities making these really amazing projects. Like, they rebuild, like, the Game of Thrones world or New York City...it had to succeed as a game first.”

Player Driven host Greg Posner circled back to the question of whether Second Life is a game, and if not, how a noob would know what to do once they’re there.

“Well, that was, that’s kind of the hilarious paradox,” Au answered. “It is such a huge, challenging onboarding experience, but if you get past the first three hours, you never leave.”

“There’s a community. The active user base is still about 600,000…Second Life is about as popular now as it was in 2006, 2008, when it was on the TV show, The Office, and people were making movies about it.”

“The main way you get past all of those onboarding hurdles is you meet someone in Second Life and they help you out,” Au said. “If you’re one of the lucky few who can actually meet someone who engages with you, and then they start taking you around and showing you everything, like, it’s ridiculously deep.”

“People don’t know this: Second Life is the largest contiguous virtual world. You can walk from one part of Second Life to the other it would take you days and days, because it’s about the size of Los Angeles right now. And so, yeah, it still has this kind of amazing quality.”

“Now it’s finally on mobile,” Au added. “They also launched a streaming service…I’m talking with them about, you know, improving that even more, just to get it, like, immediately fun and immediately amazing.”

We then pivoted to ask Au how Roblox and Fortnite fit into the metaverse.

Relative to Second Life, Au answered, “they’re very fun, immediately, in a multiplayer experience….With Roblox, you can instantly jump in on a phone, and also with Fortnite. And so you can bring in your friends, your real-life friends, your real-life family members.”

“Roblox is targeting, at least to start, a younger, much younger player base [than] Fortnite.” said Au. On the latter platform, “You go in and you’ve got the Battle Royale, and it’s immediately challenging...That’s more for, you know, teens and young 20s.”

Au came back to the UCG aspect of the metaverse, which in Fortnite’s case is its UEFN option.

“The metaverse is a ‘third space’ that happens to be online,” Au told us. “Third space, the sociological concept, [is] like, there’s a bar, a neighborhood bar or a park, a place where you are not, you know, your work self or your home self. You’re kind of in this place where you can socialize broadly with a lot of people…You go to a bar and there’s games to play or, you know, in the park, there’s Frisbee.”

There are many “Second Life merchants who make high quality 3D content. And they make a really good living...The high-end folks will make literally millions of dollars on virtual fashions and other items,” Au told us.

“You can have financial stuff happen later,” he added, but these platforms must first “get that ‘immediately fun’ and a multiplayer aspect” right, or it won’t work.

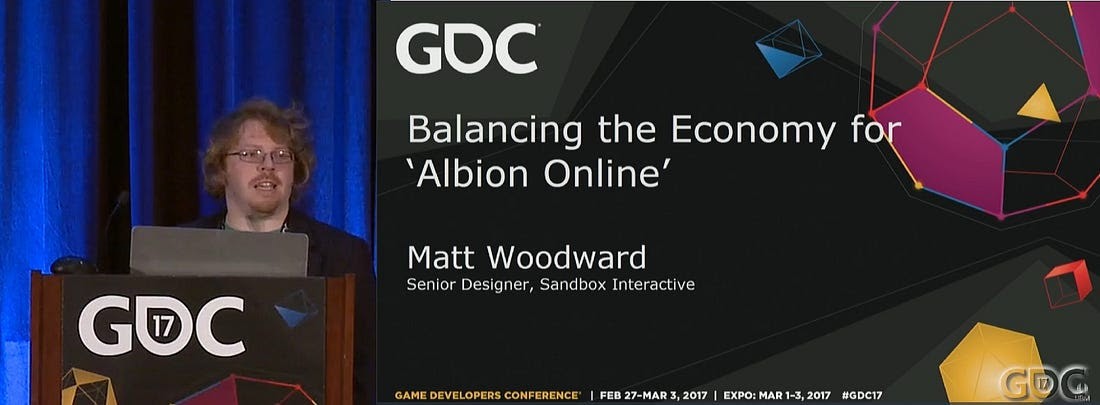

At that point, I told Au that I’d watched a GDC Vault video recently by a game designer who talked about the psychological idea of intrinsic and extrinsic needs and rewards in a social video game context. The gist of the presentation was that gamers tend to be far more motivated to engage with a game world if it delivers intrinsic rewards to them, meaning that the game’s core game loop, and the overall experience, induces feeling of happiness, joy, progress, and/or meaningful social connection.

|

Game designer Matt Woodward delivered a session on how Albion Online, an MMORPG, was designed to deliver intrinsic (and extrinsic virtual) rewards to players at Game Developers Conference 2017. (If you have a subscription, this outstanding GDC Vault video is here.)

From this vantage point, I added, virtual words like Decentraland are focused on delivering extrinsic rewards, which includes things such as monetary gains. I asked Au if he agreed that an overemphasis on extrinsic reward systems is a fundamental mistake in the metaverse.

“Yeah, totally,” he responded. “I mean, that was a big buzzword a few years ago, ‘play to win,’ with this idea that people would play so they could earn cryptocurrency or NFTs. And, like, none of these things took off.”

“Gamers themselves hated it,” Au added. “They feel like...‘You’re just trying to monetize me...’”

I pointed out that many people who’ve reviewed the rise and fall of Axie Infinity in the early 2020s compared the game’s economy to a Ponzi scheme.

“That’s a notable one,” Au confirmed. “I posted about that on my blog…Folks in the Philippines that are literally poor in real life, but they’re playing this game on mobile because, you know, they can make some money off of it.”

Axie Infinity certainly had other problems too—most notably, a $600 million crypto hack by North Korean thieves—but the bottom line is that the market value of Axie Infinity’s main token, AXS, peaked out at well over $100 for much of 2021 and 2022 and has since averaged <$10 since the beginning of 2023. AXS is currently worth about $2. Is this where Decentraland and all other Web3-focused, irl financial gain oriented virtual worlds are headed?

We’ve gotten ahead of ourselves again.

Au noted a different metaverse platform has been doing a far better job getting the community and the “onboarding to fun” angles right: VRChat.

“They’re doing incredible things,” Au told us. “And it’s larger than Second Life…In the book I said upwards of 10 million [VRChat users]. It might be a little bit less, but they have a very large user base…mostly [on] VR headsets.”

“Meta realized that VRChat was kicking their ass. Like, they launched Horizon Worlds, but then they looked at the user numbers, and VRChat was way more popular on their own platform.”

When, Where, and How Metaverse Execution Turned South

You might remember [Mark] Zuckerberg created an avatar that looked exactly like him. That, to me, was a perfect illustration of “He has no idea what the F he’s doing with the metaverse.”—James Au

Author and metaverse guru James Au wasted no time pointing the finger of blame at Meta Platforms for damaging the concept of the metaverse due to poor execution, at best, since Meta dove headfirst into this area of the social web in 2021.

According to a recent Yahoo Finance article, Meta’s Reality Labs division has since lost around $73 billion, and, as noted earlier, Meta very recently pulled back and let roughly 1,000 workers go from this division.

“Zuckerberg has done tremendous damage to the metaverse as a concept, and a vision, and also, really, as an ideal,” Au told Greg and me during our December 2025 exchange.

“The metaverse, if anyone thinks about it at all, it’s something that Meta wants to build, as opposed to being this vision of bringing people together of all races, all nationalities, together in the same virtual world space.”

“It’s immersive,” Au added. “You feel a deeper connection to them than in social media. And also for people who are disabled, like I mentioned. A lot of LGBT people are in metaverse platforms, like in VRChat.”

Zuckerberg defined his metaverse vision based on, “Well, we bought the Oculus headset, we turned it into the Quest headset.” And they thought that would be, like, the next smartphone. And so they kind of threw off, they threw out this term, metaverse, without really understanding it.

Meta launched Horizon Worlds at the end of 2021 but as Au discusses “in the book, they basically ignored most of the lessons from virtual world developers…on community” best practices, to take one example.

“One of the very first things that happened was a female journalist got sexually assaulted,” Au told us. “Her avatar was dry humped from all directions by various people. And there was a guy at Linden Lab [Jim Purbrick, who]…joined Meta, and he was telling the company, ‘This is the first thing that’s going to happen. You have to plan around that.’ And they just ignored him.”

“John Carmack was there” at Meta too, Au pointed out. “He’s been trying to build a metaverse since the early ‘90s. And they all got sidelined. So they’ve [Reality Labs’ execs] been making mistake after mistake. And yeah, they’re going in other weird directions now. They’re kind of saying, ‘Well, now the metaverse is recreating your real-life living room.’”

I noted that I have a pair of Ray-Ban Meta Glasses and that the company has been crowing about its AI-related features in recent years.

Au was not impressed.

“I have no idea why they think they can get around the creeper geek aspect, the, you know, ‘glasshole’ issue...That’s already happening. People are wearing it. Well, it’s dudes wearing it with a camera on so they can creep on women.”

Not that everything has always gone swimmingly even for the OG metaverse example, Second Life. Earlier, we addressed its game/nongame conundrum as well as its onboarding challenges. I used this opportunity speak to Au to climb into the wayback machine and revisit two other cases of what I, at least, perceived to be Linden Labs shooting Second Life in the foot early on, and therefore, potentially, crippling its own long-term growth.

The first episode involved the actions of the virtual banks that cropped on the platform. The second was the spread of unregulated gambling. Thankfully, Au was willing to travel back down some of Second Life’s seedier side streets.

I started by noting that Wired and many other publications chronicled the collapse of Ginko Financial in 2007. That “bank” had appeared in Second Life, collected roughly $750,000 worth of resident deposits, and imploded soon thereafter, taking depositors’ funds with it. I also noted that the FBI, reportedly, came sniffing around for evidence of online fraud.

“This is the flip side to wanting to create a Burning Man ideal, a complete open society,” Au told Greg and me. “Like, if you make it as free as possible, you’re going to have bad actors.”

Second Life “made it possible to convert Linden Dollars, as the virtual currency, into U.S. dollars. You could sell it.”

“Eventually, Linden Lab took that over, called it the Lindex, where you would sell it, so they could control the supply of Linden Dollars.”

Continued Au, “Some people said, ‘Okay, well, then we’re going to have gambling. We’re going to have casinos because, you know, you can sell the Linden Dollars for U.S. dollars.’”

“Then, yeah, you had unregulated banks like Ginko popping up, where Ginko…I don’t want to say it was a Ponzi scheme, but like it was offering high returns on investment.”

“Eventually there was, like, a run on the bank…[Like the 1946 film] It’s a Wonderful Life, you know, there’s a whole line of people that Jimmy Stewart and [others were in], but in Ginko’s case, it was like robots and supermodels and furries and so on trying to get their money out.”

|

An unfaithful recreation of the run on Second Life’s Ginko Financial bank in 2007, courtesy of ChatGPT’s image creator.

“That was kind of one of the first hard lessons Linden Lab had to learn,” Au continued. “If you have this open world, you’re going to have these, you know, controversies.”

“Eventually [Linden Lab] said, ‘Look, no, you can’t open a bank in Second Life unless you actually are a bank or you are licensed to have a bank in real life as well.’ And yeah, so those all went away.”

I then asked Au how the broader Second Life community responded to the disappearance of all in-world “banks.”

“I don’t think it caused long term-damage,” Au answered. “It definitely caused...unrest for a few months, but...it didn’t really impede what people were there to do...Go to, you know, fashion events and nightclubs or, you know, build steampunk societies and so on.”

“I think it was more of a collective shrug because there was already an established community of people who were already there to interact with each other...”

I then switched to the topic of gambling, which has also cropped up and grown on Second Life in the mid-2000s. I asked Au how the appearance of casinos and slot machines so so on impacted that metaverse’s residents. Per a discussion I’d had with Philip Rosedale in early 2025, I added, Rosedale told me that the Second Life economy temporarily shrunk by around 40% after Linden Labs banned gambling by introducing a skill-based gaming policy.

“I don’t have the access to the numbers that he [Rosedale] does,” Au answered, “but I will say the active user base remained solid. Like, you had some people [who] left but, like I’ve always said, the user concurrency and so on has basically remained steady.”

“There were people who left because there was no longer, you know, casinos and stuff. And now they have regulated skill gaming…It doesn’t seem to be large a part of the virtual world.”

Then as now, some U.S. states have laws banning online gambling in its entirety, and all U.S. state bans gambling among minors. Before 2007, Second Life had few, if any, guardrails around who could gamble, via the Lindex exchange, irl money.

“With the economy, you know, those people left…They cashed in their Lindens [but] the Linden Dollar supply has remained stable.”

“Inflation-wise, [the] value of the Linden Dollar has always been about 250 Linden Dollars to one U.S. dollar. So, yeah, it was kind of a temporary trend….some people were into, but it really didn’t affect the active user base…[Gambling] was never really a main part of the economy.”

Given the banking and gambling shenanigans that went on in the late 2010s in Second Life—and in the real-world in the Great Recession timeframe—I then asked Au if Second Life residents felt whiplashed as they ping-ponged between on-platform financial system scandals and irl financial system scandals in the 2006-2010 timeframe. (To be clear, a stock market also appeared in Second Life, SLCapEx, and it skyrocketed in value before crashing in late 2009, wiping out virtually all investors.)

“There was the housing crash,” Au recalled, as he pondered the parallels. “It really hurt the real-life economy, and you can play Second Life for free. So a lot of people would just still play Second Life, it’s just that they’re going to spend less money” during an irl recession.

Au recalled that businesses also pulled back their on-platform marketing spend in the Great Recession.

“I remember one of the top…marketing guys was like, ‘Hey, we’re, we’re going to have to start pulling back.’ Because, you know, that’s the first thing to go during a, you know, economic crisis, is the marketing. So yeah, that caused a big dent.”

“I guess what you can definitely say is the virtual banks that were in Second Life, they weren’t there to be part of the community,” said Au. “They were there to, you know, make a quick profit. And so, you know, we did not have that ‘too big to fail’ aspect that we did in the real life economy.”

“If you did that with the real-world economy,” and allowed the biggest banks and financial institutions to crash and burn, like Ginko (and SLCapEx) did, “it would be much more challenging. But, you know, since it is a virtual world and you’re there to role play and have fun…Your rent, or paying other bills is not dependent on being in the virtual world…You’re not as attached if the virtual banks go away.”

Fair enough.

Both sets of crises, however, strongly implied that insufficient checks on financial system transactions is a threat to the stability of metaverses and irl societies and economies alike. This, it appears, is a third clear area where metaverses have the potential to go off the rails specifically because of their tighter connections to irl financial markets. If you give metaverse users and institutions the latitude to go around or subvert the basic rules of a fair, competitive market system in order to turn a quick buck, why wouldn’t they take the money and run at the expense of the broader market system? You don’t need Web3 to get rug pulled. Second Life—and the irl megabanks that induced the Great Recession’s home mortgage crisis in the U.S.—showed that it’s entirely possible, sans NFTs, if the “rules of the game” allow it.

Might a Snow Crash 2.0 Vision Put the Metaverse Back On Its Original, Utopic Path?

Have faith in communities and community creators because there’s just and untapped wealth of people doing amazing things. And companies have to be willing to step back and let the community come forward and, sort of, form organically. And you want, you know, some regulations to prevent toxic behavior but, you know, if you foster community and foster diversity, you will succeed and it’ll be amazing.—James Au

Having gone down the rabbit hole of some of Meta’s and Second Life’s design and execution mistakes over the years, I then asked Au if there were other general lessons that could be drawn from these costly misadventures.

“I hope other metaverse platforms follow in Linden Lab’s footsteps,” Au answered. “You can have a tightly regulated economy where users can sell their currency to each other, and also make it easier to build businesses.”

He noted that, in his book, he discussed “the metaverse as a concept and then there’s the execution, which is individual metaverse platforms. Second Life is probably the one with the most open, still to this day, economy, where you can quickly exchange Linden Dollars for U.S. dollars.”

“Most of the other metaverse platforms like Roblox, you can buy Robux [there, and] Fortnite has its own, though it’s [V-Bucks are also bought] directly from the company. And you can’t easily sell it from user to user. So, that’s one way they’ve controlled the economy, I think, to the detriment of the community, because that that makes it harder to set up businesses as an individual creator.”

“The big lesson here was with the…cryptoverse folks,” Au continued, “because they were, you know, they’re the ones that have to deal with the various rug pulls. Because the whole idea, like, as we’re talking about, that [others]…can take your NFTs and you’re trying to make a killing. So, it’s got to be a lot of fluff and scam to get that rug pull possibility. So yeah, that’s been the big lesson.”

|

Moreover, “you have to be very...careful about how you control the, the whole supply of Linden Dollars or [some] other virtual currency. That actually happened with the pandemic. During the pandemic, there was…slight growth in the Second Life user base. A lot of people who played Second Life years ago…they’re all trapped...in the house, so they went back in. And so you saw a spike in people purchasing Linden Dollars.”

“The spike kind of dropped off after the pandemic,” Au continued, but “the Linden Dollar, for a while, was a little less valuable.”

“They’ve had to decrease the virtual currency supply in Second Life to stabilize it, which they did recently…That’s why they have a full-time economist at Second Life, or at Linden Lab, working for them.”

So, apart from taking a page from Second Life’s relatively open UGC economic system, Au’s advice is for other metaverse platforms that emphasize UGC monetization to hire an economist to help ensure that on-platform economic transactions and the value of the associated virtual currency remain fairly stable over time.

This isn’t unheard of—the MMO EVE Online has had an in-house economist who’s published quarterly economic performance reports for almost as long as Second Life has been around. If you’re managing any highly-sophisticated market-based economic system, it can rapidly go sideways unless you’re collecting vital metrics and have an effective toolset that can quickly rebalance the economy if and when it exceeds certain well-defined, health performance ranges.

A third point is to check the trolls.

Au told us that the “social aspect” of Meta’s Horizon Worlds has “never been addressed. And you can’t just assume it’s going to go away because you’re Meta. But I really think he’s [Zuckerberg’s] in that big of a bubble that he doesn’t realize that these issues still exist.”

“VRChat has a karmic system where you have more and more access to the virtual world based on how you how long you are in there and your behavior,” Au pointed out. “You can ignore the noobs who just joined, and you have to actually earn, you have to prove that you’re not an a-hole to be able to have full interactivity into VRChat.”

Good advice.

“There’s ways of doing it. But, yeah, you have to think about that first.”

“Really, it’s about, as we’re saying, make a fun experience, make an experience that serves the online community, encourage diversity, not only of, you know, all people of all the walks of life, but people from all over the world and age ranges and so on.”

The vision, Au maintains, is to also “make it very easy for people to create and, like, create immediately.”

“It’s in Snow Crash that there are diverse avatars. There’s a dragon. There’s a 20-foot penis. There’s just all kinds of avatars. And it’s not simply because people are having fun and playing. It’s also [that] they’re expressing their personality. They’re figuring out who they want to be in real life and how they want to express themselves.”

If you understand how metaverses differ from the 2D websites and social networking services of today, and if you put in the time and effort necessary to tap into the potential upsides of these differentiators in a safe and inclusive way, Au maintains, “you’ll be totally surprised by the amount of creativity that people will come up with.”

Utopia, here we come.

Metaverse platforms have to succeed as communities first before you impose the financial stuff. Because if you put the financial stuff there, people end up…They’re there to make money...You don’t want that. You want people to be, you know, hanging out with each other, meet each other. Like, I would like to be friends with someone from the Philippines and know about them and they know about me. And, you know, all that goes away if you have just this big financial imposition on the whole experience.—James Au

James Au, author of the insightful and entertaining 2023 book, Making a Metaverse That Matters, was a guest on Player Driven in December. Au didn’t pull any punches when it came to a topic that’s been near and dear to his heart for two decades: the metaverse.

Yes, the metaverse.

Despite what you may have read or heard, or perhaps experienced first-hand in recent years, the metaverse is indeed alive and kicking. In fact, according to Au, it’s on a comeback tour now that Meta has taken a huge step back from its 4+ yearlong “all metaverse all the time” messaging and investment strategy (and pivoted to AI).

Au, who hails from Kailua, a beach town not far from Honolulu on the Hawaiian island of O’ahu, has been as enmeshed as anyone in all things metaverse since Second Life debuted in 2003. Author of three books and numerous articles featured in The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, Wired, Gigaom and other publications, Au currently lives in Los Angeles and additionally consults with metaverse-related companies.

The first question that Player Driven host Greg Posner put to Au was how he was drawn into the metaverse at a time when he was surrounded by virtually infinite irl sun and sand.

“I would go surfing or play beach volleyball in the day,” Au responded, grinning wryly. “I love Hawaii and it’s always home. It is paradise.”

“As a hardcore geek, I would, you know, be really wanting to see what the latest game is. You enjoy Hawaii in all its splendor in the daytime, and then you wait until it gets dark when, you know, you get your graphic display working really well. So yeah, I just tried to mix both…the best of the real world, best of the virtual world.”

That sounds rough.

I was excited to be a co-host on this Player Driven episode because I was a Second Life resident (briefly) in the late 2000s, remember the experience with fondness, and I wanted to pick Au’s brain on what this OG metaverse instance was—and is—about in a broad, long-term sense. As an official embedded reporter (Linden Lab, maker of Second Life, hired him to chronicle events and news there) for many years, few people on Earth or in the metaverse are better positioned than Au to put the lay of that particular piece of virtual land into context.

My first question to Au, though, was about a higher-level topic that he raised early in his 2023 book, which he was gracious enough to share with me.

In Making a Metaverse That Matters, Au wrote, there are over half a billion regular metaverse users, led by several social gaming platforms such as Roblox, Minecraft, and Fortnite. These, and their smaller metaverse cousins, “share five core features that are integral and unique,” according to Au, and these generally yield better user experience than the 2D websites and virtual communities most of us grew up with and continue to use today.

Regarding these five metaverse-defining features, Au responded, one was that a “metaverse is a vast virtual world. It’s highly immersive, which could mean a VR headset or no VR headset…It’s either 3D on your screen or on your headset, but mostly it’s going to be, you know, on a flat screen, like on a mobile, or your desktop, or a console.”

The second and third differentiators are that metaverses have “highly customizable avatars and creation tools, which is very important.”

In the book, Au noted that avatars help create a sense that users are part of a virtual world and can be perceived by others in it at the same time. A experiment run at Stanford University years ago, he also noted, showed that most avatar users felt such an intuitive connection with their avatars’ perspective that they recreated unconscious social rules, as if these avatars were an extension of their real-life selves, a key difference from the typical anonymous (well, with cookies) web surfing experience.

Turning to the UGC (user-generated content) angle, Au told us that Roblox, Minecraft, Fortnite, and other metaverse platforms, have deep and rich feature sets that allow users to remake entire worlds or build new ones from scratch (mostly on PCs), and publish them for others to experience and share.

|

Left to right: Greg Posner, Wagner James Au, Lewis Ward.

The forth differentiator, Au said, is that metaverse platforms are “connected to the real world economy and off-world or non-virtual world technology. So, in practical terms, that means it’s integrated with...The virtual currency…is connected to the real world economy in the sense that you could cash out your virtual currency.”

Check. It’s true that platforms like Roblox, Minecraft, Fortnite and Second Life all support creators who make good irl livings by building objects and experiences that other players/users pay for directly or indirectly. (Player Driven fans may recall that we profiled a Overwolf/CurseForge creator of ARK: Survival Ascended mods who routinely cleared >$15,000 a month last year, so this UGC monetization angle isn’t exclusive to the metaverse platforms.)

Last, Au said that metaverses have “the capacity to contain many millions of people. So one advantage of that is you can meet people from all over the world.”

He underscored the importance of this social angle and also highlighted its accessibility elements.

“A lot of people who use metaverse platforms are physically disabled for many reasons, and are able to connect [there]. For example, there’s technology now…You can connect your brain to a virtual world and can control it there. Or if you’re disabled, you can still have ways of connecting within the virtual world. And, you know, that becomes your social channel in a lot of ways.”

Three of Au’s five metaverse differentiators have ties to their rich social capabilities: avatars, UCG tools, and direct social networking and communication (friends lists, voice and text chat, etc.).

“The thing about avatars,” Au added, “and I say that as part of the definition, ‘highly customizable,’ is, to your point, [that] a lot of people go into a virtual world space and you are engaging with millions of people that are strangers. And so, you know, people are uncomfortable with expressing who they are in real life, often. And so they want to experiment with what their identity is…That’s an also important thing” in metaverses relative to most online communities and websites.

“The game industry is sort of confused why Roblox is really huge,” Au continued. “And I’m, like, pulling my hair out. It’s because it’s a metaverse platform.”

“It’s not only [that] you’re able to create interactive experiences, but you have hundreds of millions of people. There’s 360 million monthly active users in Roblox. And also you have all this high degree of customizability.”

“So, unlike Steam, where you create a game and if you’re to update it, it’s a whole arduous process...[On Roblox] you can adjust it based on literally millions of people interacting with it, and get really interesting interactivity, and then [make] improvements that you can do on the fly.”

Au’s thoughts drifted back to Second Life. That metaverse “is a community. The people, they actually know each other in Second Life, and they end up meeting in real life. There was a Second Life convention. So people would actually go to Chicago or New York or San Francisco to meet people.”

Au believes that the social side of metaverses is a huge factor in their stickiness.

“With the metaverse, it’s other people to a great extent. It’s people that you meet from all walks of life” that’s at the root of why millions of users come back weekly, if not daily, year after year, to these environments.

“So, yeah, those are the five things. And that’s taken directly from [Neal Stephenson’s] Snow Crash, the novel, because that really inspired the whole metaverse wave and it actually envisioned the whole metaverse.”

“Unfortunately, [Meta’s] Mark Zuckerberg and some other folks within the tech industry sort of forgot that that’s what we were all trying to build, and people like [Epic Games’] Tim Sweeney have been trying to build since the early nineties.”

We’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Read on, if you’d like Au’s takes on:

What Second Life, Roblox, and Fortnite have gotten right

Where some prominent metaverse platforms have fallen flat

How leading metaverses can shore up some key shortcomings to help unlock their latent potential

Oh, and if you’re not subscribed to our newsletter, what’s the holdup?

Where Second Life, Roblox, and Fortnite Stand As Metaverse Standard-Bearers

What Second Life did right was getting the community there first, and making sure people really wanted to be there to hang out with each other and to be friends with each other…That’s kind of been the problem with the...I call it the cryptoverse. Virtual worlds that are linked to NFTs or cryptocurrency, none of them have really taken off because of this problem. It’s like, if you are saying that you’re there with the idea, like, in Decentraland, that your property is going to be super valuable at some point, and you can sell it off, then people are only there for the profit motive. They’re not there to hang out with other people and meet other people, and make friends and work on creative projects. So, yeah, they’ve kind of gone nowhere because of that…People are already there for the wrong reasons.—James Au

Two big takeaways from James Au’s assessment of today’s top metaverse examples were that (1) they nail the community support elements and (2) they onboard noobs into the sticky fun and social goo as quickly as possible.

We began by discussion what Second Life got right back in the day.

“It was the first platform to reach mainstream awareness that really was trying to capture the whole metaverse experience,” Au explained to Greg and me. “Everything I mentioned of, you know, highly customizable avatars, creation tools you could [use to] build immediately…”

“This is even before Minecraft. You could actually just construct a 3D, you know, building a castle or a spaceship or whatever, and then there’s physics and there’s scripting so you can actually create, make it interactive. That’s the first, like, actual platform to show all of that and show what was possible, and it immediately got people excited from all walks of life.”

“As a reporter” in Second Life, Au continued, “I met people, like, who are artists and academics and, yeah, people who are not only gamers. They were seeing this. Well, you know, most of them had read Snow Crash, so they saw where this was going.”

Not long after the “eyeballs” arrived in the early- to mid-2000s, companies and nonprofits began showing up and staking out a presence on the platform.

In Second Life, Au recalled, “a lot of companies started putting up headquarters and creating marketing experiences, like American Apparel and Coca-Cola and so on.”

“What they [Linden Lab] got right is really capturing the vision and showing there is an interest in it. And then I go into the flip side of what they didn’t get right.”

“Is Second Life a game?” Au asked. “It’s still this philosophical question that generates a huge amount of arguments…You know, I love Philip Rosedale. He’s brilliant.”

“He’s not a gamer. So, he wanted it to be like a online Burning Man because he’s a big Burning Man guy,” Au explained. “I’ve talked to Philip about that.”

|

Left: Linden Lab founder Philip Rosedale. Right: Avatars in Second Life having a snowball fight…and dancing.

“It’s like, ‘Philip, yeah, Burning Man is really cool, but Only 50,000 people go to Burning Man, and it tends to be fairly wealthy folks. And it’s, like, you’re not going to [get] a whole diverse group of people to go into this thing if you’re going for that Burning Man thing,’” said Au.

“Minecraft launched a few years after Second Life and because it was a fun game experience to start with, now you have schools using it. You have communities making these really amazing projects. Like, they rebuild, like, the Game of Thrones world or New York City...it had to succeed as a game first.”

Player Driven host Greg Posner circled back to the question of whether Second Life is a game, and if not, how a noob would know what to do once they’re there.

“Well, that was, that’s kind of the hilarious paradox,” Au answered. “It is such a huge, challenging onboarding experience, but if you get past the first three hours, you never leave.”

“There’s a community. The active user base is still about 600,000…Second Life is about as popular now as it was in 2006, 2008, when it was on the TV show, The Office, and people were making movies about it.”

“The main way you get past all of those onboarding hurdles is you meet someone in Second Life and they help you out,” Au said. “If you’re one of the lucky few who can actually meet someone who engages with you, and then they start taking you around and showing you everything, like, it’s ridiculously deep.”

“People don’t know this: Second Life is the largest contiguous virtual world. You can walk from one part of Second Life to the other it would take you days and days, because it’s about the size of Los Angeles right now. And so, yeah, it still has this kind of amazing quality.”

“Now it’s finally on mobile,” Au added. “They also launched a streaming service…I’m talking with them about, you know, improving that even more, just to get it, like, immediately fun and immediately amazing.”

We then pivoted to ask Au how Roblox and Fortnite fit into the metaverse.

Relative to Second Life, Au answered, “they’re very fun, immediately, in a multiplayer experience….With Roblox, you can instantly jump in on a phone, and also with Fortnite. And so you can bring in your friends, your real-life friends, your real-life family members.”

“Roblox is targeting, at least to start, a younger, much younger player base [than] Fortnite.” said Au. On the latter platform, “You go in and you’ve got the Battle Royale, and it’s immediately challenging...That’s more for, you know, teens and young 20s.”

Au came back to the UCG aspect of the metaverse, which in Fortnite’s case is its UEFN option.

“The metaverse is a ‘third space’ that happens to be online,” Au told us. “Third space, the sociological concept, [is] like, there’s a bar, a neighborhood bar or a park, a place where you are not, you know, your work self or your home self. You’re kind of in this place where you can socialize broadly with a lot of people…You go to a bar and there’s games to play or, you know, in the park, there’s Frisbee.”

There are many “Second Life merchants who make high quality 3D content. And they make a really good living...The high-end folks will make literally millions of dollars on virtual fashions and other items,” Au told us.

“You can have financial stuff happen later,” he added, but these platforms must first “get that ‘immediately fun’ and a multiplayer aspect” right, or it won’t work.

At that point, I told Au that I’d watched a GDC Vault video recently by a game designer who talked about the psychological idea of intrinsic and extrinsic needs and rewards in a social video game context. The gist of the presentation was that gamers tend to be far more motivated to engage with a game world if it delivers intrinsic rewards to them, meaning that the game’s core game loop, and the overall experience, induces feeling of happiness, joy, progress, and/or meaningful social connection.

|

Game designer Matt Woodward delivered a session on how Albion Online, an MMORPG, was designed to deliver intrinsic (and extrinsic virtual) rewards to players at Game Developers Conference 2017. (If you have a subscription, this outstanding GDC Vault video is here.)

From this vantage point, I added, virtual words like Decentraland are focused on delivering extrinsic rewards, which includes things such as monetary gains. I asked Au if he agreed that an overemphasis on extrinsic reward systems is a fundamental mistake in the metaverse.

“Yeah, totally,” he responded. “I mean, that was a big buzzword a few years ago, ‘play to win,’ with this idea that people would play so they could earn cryptocurrency or NFTs. And, like, none of these things took off.”

“Gamers themselves hated it,” Au added. “They feel like...‘You’re just trying to monetize me...’”

I pointed out that many people who’ve reviewed the rise and fall of Axie Infinity in the early 2020s compared the game’s economy to a Ponzi scheme.

“That’s a notable one,” Au confirmed. “I posted about that on my blog…Folks in the Philippines that are literally poor in real life, but they’re playing this game on mobile because, you know, they can make some money off of it.”

Axie Infinity certainly had other problems too—most notably, a $600 million crypto hack by North Korean thieves—but the bottom line is that the market value of Axie Infinity’s main token, AXS, peaked out at well over $100 for much of 2021 and 2022 and has since averaged <$10 since the beginning of 2023. AXS is currently worth about $2. Is this where Decentraland and all other Web3-focused, irl financial gain oriented virtual worlds are headed?

We’ve gotten ahead of ourselves again.

Au noted a different metaverse platform has been doing a far better job getting the community and the “onboarding to fun” angles right: VRChat.

“They’re doing incredible things,” Au told us. “And it’s larger than Second Life…In the book I said upwards of 10 million [VRChat users]. It might be a little bit less, but they have a very large user base…mostly [on] VR headsets.”

“Meta realized that VRChat was kicking their ass. Like, they launched Horizon Worlds, but then they looked at the user numbers, and VRChat was way more popular on their own platform.”

When, Where, and How Metaverse Execution Turned South

You might remember [Mark] Zuckerberg created an avatar that looked exactly like him. That, to me, was a perfect illustration of “He has no idea what the F he’s doing with the metaverse.”—James Au

Author and metaverse guru James Au wasted no time pointing the finger of blame at Meta Platforms for damaging the concept of the metaverse due to poor execution, at best, since Meta dove headfirst into this area of the social web in 2021.

According to a recent Yahoo Finance article, Meta’s Reality Labs division has since lost around $73 billion, and, as noted earlier, Meta very recently pulled back and let roughly 1,000 workers go from this division.

“Zuckerberg has done tremendous damage to the metaverse as a concept, and a vision, and also, really, as an ideal,” Au told Greg and me during our December 2025 exchange.

“The metaverse, if anyone thinks about it at all, it’s something that Meta wants to build, as opposed to being this vision of bringing people together of all races, all nationalities, together in the same virtual world space.”

“It’s immersive,” Au added. “You feel a deeper connection to them than in social media. And also for people who are disabled, like I mentioned. A lot of LGBT people are in metaverse platforms, like in VRChat.”

Zuckerberg defined his metaverse vision based on, “Well, we bought the Oculus headset, we turned it into the Quest headset.” And they thought that would be, like, the next smartphone. And so they kind of threw off, they threw out this term, metaverse, without really understanding it.

Meta launched Horizon Worlds at the end of 2021 but as Au discusses “in the book, they basically ignored most of the lessons from virtual world developers…on community” best practices, to take one example.

“One of the very first things that happened was a female journalist got sexually assaulted,” Au told us. “Her avatar was dry humped from all directions by various people. And there was a guy at Linden Lab [Jim Purbrick, who]…joined Meta, and he was telling the company, ‘This is the first thing that’s going to happen. You have to plan around that.’ And they just ignored him.”

“John Carmack was there” at Meta too, Au pointed out. “He’s been trying to build a metaverse since the early ‘90s. And they all got sidelined. So they’ve [Reality Labs’ execs] been making mistake after mistake. And yeah, they’re going in other weird directions now. They’re kind of saying, ‘Well, now the metaverse is recreating your real-life living room.’”

I noted that I have a pair of Ray-Ban Meta Glasses and that the company has been crowing about its AI-related features in recent years.

Au was not impressed.

“I have no idea why they think they can get around the creeper geek aspect, the, you know, ‘glasshole’ issue...That’s already happening. People are wearing it. Well, it’s dudes wearing it with a camera on so they can creep on women.”

Not that everything has always gone swimmingly even for the OG metaverse example, Second Life. Earlier, we addressed its game/nongame conundrum as well as its onboarding challenges. I used this opportunity speak to Au to climb into the wayback machine and revisit two other cases of what I, at least, perceived to be Linden Labs shooting Second Life in the foot early on, and therefore, potentially, crippling its own long-term growth.

The first episode involved the actions of the virtual banks that cropped on the platform. The second was the spread of unregulated gambling. Thankfully, Au was willing to travel back down some of Second Life’s seedier side streets.

I started by noting that Wired and many other publications chronicled the collapse of Ginko Financial in 2007. That “bank” had appeared in Second Life, collected roughly $750,000 worth of resident deposits, and imploded soon thereafter, taking depositors’ funds with it. I also noted that the FBI, reportedly, came sniffing around for evidence of online fraud.

“This is the flip side to wanting to create a Burning Man ideal, a complete open society,” Au told Greg and me. “Like, if you make it as free as possible, you’re going to have bad actors.”

Second Life “made it possible to convert Linden Dollars, as the virtual currency, into U.S. dollars. You could sell it.”

“Eventually, Linden Lab took that over, called it the Lindex, where you would sell it, so they could control the supply of Linden Dollars.”

Continued Au, “Some people said, ‘Okay, well, then we’re going to have gambling. We’re going to have casinos because, you know, you can sell the Linden Dollars for U.S. dollars.’”

“Then, yeah, you had unregulated banks like Ginko popping up, where Ginko…I don’t want to say it was a Ponzi scheme, but like it was offering high returns on investment.”

“Eventually there was, like, a run on the bank…[Like the 1946 film] It’s a Wonderful Life, you know, there’s a whole line of people that Jimmy Stewart and [others were in], but in Ginko’s case, it was like robots and supermodels and furries and so on trying to get their money out.”

|

An unfaithful recreation of the run on Second Life’s Ginko Financial bank in 2007, courtesy of ChatGPT’s image creator.

“That was kind of one of the first hard lessons Linden Lab had to learn,” Au continued. “If you have this open world, you’re going to have these, you know, controversies.”

“Eventually [Linden Lab] said, ‘Look, no, you can’t open a bank in Second Life unless you actually are a bank or you are licensed to have a bank in real life as well.’ And yeah, so those all went away.”

I then asked Au how the broader Second Life community responded to the disappearance of all in-world “banks.”

“I don’t think it caused long term-damage,” Au answered. “It definitely caused...unrest for a few months, but...it didn’t really impede what people were there to do...Go to, you know, fashion events and nightclubs or, you know, build steampunk societies and so on.”

“I think it was more of a collective shrug because there was already an established community of people who were already there to interact with each other...”

I then switched to the topic of gambling, which has also cropped up and grown on Second Life in the mid-2000s. I asked Au how the appearance of casinos and slot machines so so on impacted that metaverse’s residents. Per a discussion I’d had with Philip Rosedale in early 2025, I added, Rosedale told me that the Second Life economy temporarily shrunk by around 40% after Linden Labs banned gambling by introducing a skill-based gaming policy.

“I don’t have the access to the numbers that he [Rosedale] does,” Au answered, “but I will say the active user base remained solid. Like, you had some people [who] left but, like I’ve always said, the user concurrency and so on has basically remained steady.”

“There were people who left because there was no longer, you know, casinos and stuff. And now they have regulated skill gaming…It doesn’t seem to be large a part of the virtual world.”

Then as now, some U.S. states have laws banning online gambling in its entirety, and all U.S. state bans gambling among minors. Before 2007, Second Life had few, if any, guardrails around who could gamble, via the Lindex exchange, irl money.

“With the economy, you know, those people left…They cashed in their Lindens [but] the Linden Dollar supply has remained stable.”

“Inflation-wise, [the] value of the Linden Dollar has always been about 250 Linden Dollars to one U.S. dollar. So, yeah, it was kind of a temporary trend….some people were into, but it really didn’t affect the active user base…[Gambling] was never really a main part of the economy.”

Given the banking and gambling shenanigans that went on in the late 2010s in Second Life—and in the real-world in the Great Recession timeframe—I then asked Au if Second Life residents felt whiplashed as they ping-ponged between on-platform financial system scandals and irl financial system scandals in the 2006-2010 timeframe. (To be clear, a stock market also appeared in Second Life, SLCapEx, and it skyrocketed in value before crashing in late 2009, wiping out virtually all investors.)

“There was the housing crash,” Au recalled, as he pondered the parallels. “It really hurt the real-life economy, and you can play Second Life for free. So a lot of people would just still play Second Life, it’s just that they’re going to spend less money” during an irl recession.

Au recalled that businesses also pulled back their on-platform marketing spend in the Great Recession.

“I remember one of the top…marketing guys was like, ‘Hey, we’re, we’re going to have to start pulling back.’ Because, you know, that’s the first thing to go during a, you know, economic crisis, is the marketing. So yeah, that caused a big dent.”

“I guess what you can definitely say is the virtual banks that were in Second Life, they weren’t there to be part of the community,” said Au. “They were there to, you know, make a quick profit. And so, you know, we did not have that ‘too big to fail’ aspect that we did in the real life economy.”

“If you did that with the real-world economy,” and allowed the biggest banks and financial institutions to crash and burn, like Ginko (and SLCapEx) did, “it would be much more challenging. But, you know, since it is a virtual world and you’re there to role play and have fun…Your rent, or paying other bills is not dependent on being in the virtual world…You’re not as attached if the virtual banks go away.”

Fair enough.

Both sets of crises, however, strongly implied that insufficient checks on financial system transactions is a threat to the stability of metaverses and irl societies and economies alike. This, it appears, is a third clear area where metaverses have the potential to go off the rails specifically because of their tighter connections to irl financial markets. If you give metaverse users and institutions the latitude to go around or subvert the basic rules of a fair, competitive market system in order to turn a quick buck, why wouldn’t they take the money and run at the expense of the broader market system? You don’t need Web3 to get rug pulled. Second Life—and the irl megabanks that induced the Great Recession’s home mortgage crisis in the U.S.—showed that it’s entirely possible, sans NFTs, if the “rules of the game” allow it.

Might a Snow Crash 2.0 Vision Put the Metaverse Back On Its Original, Utopic Path?

Have faith in communities and community creators because there’s just and untapped wealth of people doing amazing things. And companies have to be willing to step back and let the community come forward and, sort of, form organically. And you want, you know, some regulations to prevent toxic behavior but, you know, if you foster community and foster diversity, you will succeed and it’ll be amazing.—James Au

Having gone down the rabbit hole of some of Meta’s and Second Life’s design and execution mistakes over the years, I then asked Au if there were other general lessons that could be drawn from these costly misadventures.

“I hope other metaverse platforms follow in Linden Lab’s footsteps,” Au answered. “You can have a tightly regulated economy where users can sell their currency to each other, and also make it easier to build businesses.”

He noted that, in his book, he discussed “the metaverse as a concept and then there’s the execution, which is individual metaverse platforms. Second Life is probably the one with the most open, still to this day, economy, where you can quickly exchange Linden Dollars for U.S. dollars.”

“Most of the other metaverse platforms like Roblox, you can buy Robux [there, and] Fortnite has its own, though it’s [V-Bucks are also bought] directly from the company. And you can’t easily sell it from user to user. So, that’s one way they’ve controlled the economy, I think, to the detriment of the community, because that that makes it harder to set up businesses as an individual creator.”

“The big lesson here was with the…cryptoverse folks,” Au continued, “because they were, you know, they’re the ones that have to deal with the various rug pulls. Because the whole idea, like, as we’re talking about, that [others]…can take your NFTs and you’re trying to make a killing. So, it’s got to be a lot of fluff and scam to get that rug pull possibility. So yeah, that’s been the big lesson.”

|

Moreover, “you have to be very...careful about how you control the, the whole supply of Linden Dollars or [some] other virtual currency. That actually happened with the pandemic. During the pandemic, there was…slight growth in the Second Life user base. A lot of people who played Second Life years ago…they’re all trapped...in the house, so they went back in. And so you saw a spike in people purchasing Linden Dollars.”

“The spike kind of dropped off after the pandemic,” Au continued, but “the Linden Dollar, for a while, was a little less valuable.”

“They’ve had to decrease the virtual currency supply in Second Life to stabilize it, which they did recently…That’s why they have a full-time economist at Second Life, or at Linden Lab, working for them.”

So, apart from taking a page from Second Life’s relatively open UGC economic system, Au’s advice is for other metaverse platforms that emphasize UGC monetization to hire an economist to help ensure that on-platform economic transactions and the value of the associated virtual currency remain fairly stable over time.

This isn’t unheard of—the MMO EVE Online has had an in-house economist who’s published quarterly economic performance reports for almost as long as Second Life has been around. If you’re managing any highly-sophisticated market-based economic system, it can rapidly go sideways unless you’re collecting vital metrics and have an effective toolset that can quickly rebalance the economy if and when it exceeds certain well-defined, health performance ranges.

A third point is to check the trolls.

Au told us that the “social aspect” of Meta’s Horizon Worlds has “never been addressed. And you can’t just assume it’s going to go away because you’re Meta. But I really think he’s [Zuckerberg’s] in that big of a bubble that he doesn’t realize that these issues still exist.”

“VRChat has a karmic system where you have more and more access to the virtual world based on how you how long you are in there and your behavior,” Au pointed out. “You can ignore the noobs who just joined, and you have to actually earn, you have to prove that you’re not an a-hole to be able to have full interactivity into VRChat.”

Good advice.

“There’s ways of doing it. But, yeah, you have to think about that first.”

“Really, it’s about, as we’re saying, make a fun experience, make an experience that serves the online community, encourage diversity, not only of, you know, all people of all the walks of life, but people from all over the world and age ranges and so on.”

The vision, Au maintains, is to also “make it very easy for people to create and, like, create immediately.”

“It’s in Snow Crash that there are diverse avatars. There’s a dragon. There’s a 20-foot penis. There’s just all kinds of avatars. And it’s not simply because people are having fun and playing. It’s also [that] they’re expressing their personality. They’re figuring out who they want to be in real life and how they want to express themselves.”

If you understand how metaverses differ from the 2D websites and social networking services of today, and if you put in the time and effort necessary to tap into the potential upsides of these differentiators in a safe and inclusive way, Au maintains, “you’ll be totally surprised by the amount of creativity that people will come up with.”

Utopia, here we come.

Metaverse platforms have to succeed as communities first before you impose the financial stuff. Because if you put the financial stuff there, people end up…They’re there to make money...You don’t want that. You want people to be, you know, hanging out with each other, meet each other. Like, I would like to be friends with someone from the Philippines and know about them and they know about me. And, you know, all that goes away if you have just this big financial imposition on the whole experience.—James Au

James Au, author of the insightful and entertaining 2023 book, Making a Metaverse That Matters, was a guest on Player Driven in December. Au didn’t pull any punches when it came to a topic that’s been near and dear to his heart for two decades: the metaverse.

Yes, the metaverse.

Despite what you may have read or heard, or perhaps experienced first-hand in recent years, the metaverse is indeed alive and kicking. In fact, according to Au, it’s on a comeback tour now that Meta has taken a huge step back from its 4+ yearlong “all metaverse all the time” messaging and investment strategy (and pivoted to AI).

Au, who hails from Kailua, a beach town not far from Honolulu on the Hawaiian island of O’ahu, has been as enmeshed as anyone in all things metaverse since Second Life debuted in 2003. Author of three books and numerous articles featured in The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, Wired, Gigaom and other publications, Au currently lives in Los Angeles and additionally consults with metaverse-related companies.

The first question that Player Driven host Greg Posner put to Au was how he was drawn into the metaverse at a time when he was surrounded by virtually infinite irl sun and sand.

“I would go surfing or play beach volleyball in the day,” Au responded, grinning wryly. “I love Hawaii and it’s always home. It is paradise.”

“As a hardcore geek, I would, you know, be really wanting to see what the latest game is. You enjoy Hawaii in all its splendor in the daytime, and then you wait until it gets dark when, you know, you get your graphic display working really well. So yeah, I just tried to mix both…the best of the real world, best of the virtual world.”

That sounds rough.

I was excited to be a co-host on this Player Driven episode because I was a Second Life resident (briefly) in the late 2000s, remember the experience with fondness, and I wanted to pick Au’s brain on what this OG metaverse instance was—and is—about in a broad, long-term sense. As an official embedded reporter (Linden Lab, maker of Second Life, hired him to chronicle events and news there) for many years, few people on Earth or in the metaverse are better positioned than Au to put the lay of that particular piece of virtual land into context.

My first question to Au, though, was about a higher-level topic that he raised early in his 2023 book, which he was gracious enough to share with me.

In Making a Metaverse That Matters, Au wrote, there are over half a billion regular metaverse users, led by several social gaming platforms such as Roblox, Minecraft, and Fortnite. These, and their smaller metaverse cousins, “share five core features that are integral and unique,” according to Au, and these generally yield better user experience than the 2D websites and virtual communities most of us grew up with and continue to use today.

Regarding these five metaverse-defining features, Au responded, one was that a “metaverse is a vast virtual world. It’s highly immersive, which could mean a VR headset or no VR headset…It’s either 3D on your screen or on your headset, but mostly it’s going to be, you know, on a flat screen, like on a mobile, or your desktop, or a console.”

The second and third differentiators are that metaverses have “highly customizable avatars and creation tools, which is very important.”

In the book, Au noted that avatars help create a sense that users are part of a virtual world and can be perceived by others in it at the same time. A experiment run at Stanford University years ago, he also noted, showed that most avatar users felt such an intuitive connection with their avatars’ perspective that they recreated unconscious social rules, as if these avatars were an extension of their real-life selves, a key difference from the typical anonymous (well, with cookies) web surfing experience.

Turning to the UGC (user-generated content) angle, Au told us that Roblox, Minecraft, Fortnite, and other metaverse platforms, have deep and rich feature sets that allow users to remake entire worlds or build new ones from scratch (mostly on PCs), and publish them for others to experience and share.

|

Left to right: Greg Posner, Wagner James Au, Lewis Ward.

The forth differentiator, Au said, is that metaverse platforms are “connected to the real world economy and off-world or non-virtual world technology. So, in practical terms, that means it’s integrated with...The virtual currency…is connected to the real world economy in the sense that you could cash out your virtual currency.”

Check. It’s true that platforms like Roblox, Minecraft, Fortnite and Second Life all support creators who make good irl livings by building objects and experiences that other players/users pay for directly or indirectly. (Player Driven fans may recall that we profiled a Overwolf/CurseForge creator of ARK: Survival Ascended mods who routinely cleared >$15,000 a month last year, so this UGC monetization angle isn’t exclusive to the metaverse platforms.)

Last, Au said that metaverses have “the capacity to contain many millions of people. So one advantage of that is you can meet people from all over the world.”

He underscored the importance of this social angle and also highlighted its accessibility elements.

“A lot of people who use metaverse platforms are physically disabled for many reasons, and are able to connect [there]. For example, there’s technology now…You can connect your brain to a virtual world and can control it there. Or if you’re disabled, you can still have ways of connecting within the virtual world. And, you know, that becomes your social channel in a lot of ways.”

Three of Au’s five metaverse differentiators have ties to their rich social capabilities: avatars, UCG tools, and direct social networking and communication (friends lists, voice and text chat, etc.).

“The thing about avatars,” Au added, “and I say that as part of the definition, ‘highly customizable,’ is, to your point, [that] a lot of people go into a virtual world space and you are engaging with millions of people that are strangers. And so, you know, people are uncomfortable with expressing who they are in real life, often. And so they want to experiment with what their identity is…That’s an also important thing” in metaverses relative to most online communities and websites.

“The game industry is sort of confused why Roblox is really huge,” Au continued. “And I’m, like, pulling my hair out. It’s because it’s a metaverse platform.”

“It’s not only [that] you’re able to create interactive experiences, but you have hundreds of millions of people. There’s 360 million monthly active users in Roblox. And also you have all this high degree of customizability.”

“So, unlike Steam, where you create a game and if you’re to update it, it’s a whole arduous process...[On Roblox] you can adjust it based on literally millions of people interacting with it, and get really interesting interactivity, and then [make] improvements that you can do on the fly.”

Au’s thoughts drifted back to Second Life. That metaverse “is a community. The people, they actually know each other in Second Life, and they end up meeting in real life. There was a Second Life convention. So people would actually go to Chicago or New York or San Francisco to meet people.”

Au believes that the social side of metaverses is a huge factor in their stickiness.

“With the metaverse, it’s other people to a great extent. It’s people that you meet from all walks of life” that’s at the root of why millions of users come back weekly, if not daily, year after year, to these environments.

“So, yeah, those are the five things. And that’s taken directly from [Neal Stephenson’s] Snow Crash, the novel, because that really inspired the whole metaverse wave and it actually envisioned the whole metaverse.”

“Unfortunately, [Meta’s] Mark Zuckerberg and some other folks within the tech industry sort of forgot that that’s what we were all trying to build, and people like [Epic Games’] Tim Sweeney have been trying to build since the early nineties.”

We’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Read on, if you’d like Au’s takes on:

What Second Life, Roblox, and Fortnite have gotten right

Where some prominent metaverse platforms have fallen flat

How leading metaverses can shore up some key shortcomings to help unlock their latent potential

Oh, and if you’re not subscribed to our newsletter, what’s the holdup?

Where Second Life, Roblox, and Fortnite Stand As Metaverse Standard-Bearers

What Second Life did right was getting the community there first, and making sure people really wanted to be there to hang out with each other and to be friends with each other…That’s kind of been the problem with the...I call it the cryptoverse. Virtual worlds that are linked to NFTs or cryptocurrency, none of them have really taken off because of this problem. It’s like, if you are saying that you’re there with the idea, like, in Decentraland, that your property is going to be super valuable at some point, and you can sell it off, then people are only there for the profit motive. They’re not there to hang out with other people and meet other people, and make friends and work on creative projects. So, yeah, they’ve kind of gone nowhere because of that…People are already there for the wrong reasons.—James Au

Two big takeaways from James Au’s assessment of today’s top metaverse examples were that (1) they nail the community support elements and (2) they onboard noobs into the sticky fun and social goo as quickly as possible.